Once upon a time, in the small town of Marienburg in the Swedish Empire, there lived a girl who would have gladly traded places with Cinderella. A wicked stepmother? Mean sisters? An exceptional but not always reliable fairy godmother? Martha Skavronska could only dream of such bliss! Having lost both her parents when she was a child, Martha lived in an orphanage. If luck were on her side, one day she would become a servant and live the rest of her life scrubbing pots and doing laundry—a predictable fate for girls of her kind.

Marienburg (now Aluksne) Castle in 1661

Luck did smile on Martha when Pastor Gluck came to the orphanage and took her to his house as a ward and scullery maid. Though the pastor was a highly educated man, a scholar and a translator of the Bible, he never taught Martha to read or write. Why would a servant need those skills? He was glad that the girl was pleasant, capable and proved a good addition to the household. That was until she grew up and began to attract the attentions of the pastor’s son. To save her boy from temptation, Mrs. Gluck made the wise decision of marrying off Martha. Swedish King Karl XII was engaged in the Great Northern War with Russian Tsar Peter and had a military regiment stationed in Marienburg. The Glucks found a willing dragoon and he and Martha married. A common fairytale would end here with its typical “And they lived happily ever after.” Not this one.

Martha’s first marriage did not last long. Shortly after the wedding, the dragoon and his regiment marched out of town. Did he perish in the war or survive it? There are contradicting accounts of his fate.

Vasilyev, 1850. Pastor Gluck introduces Martha to Field Marshal Sheremetyev

In 1702, Marienburg became one of Russia’s first conquests. Field marshal Count Sheremetyev who led the Russian troops to victory, counted eighteen-year-old Martha among his trophies. She was pretty and, among other things, made an excellent washerwoman. The not-so-young Count was quite pleased with his new acquisition. That was until six months later, Count Alex Menshikov, Tsar Peter’s trusted envoy, visited the conquered Marienburg—and was conquered by Martha.

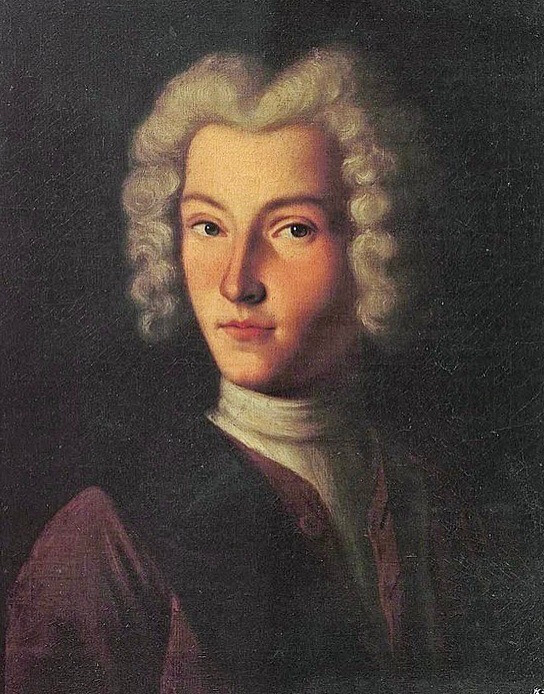

Prince Alexander Menshikov. Painting by Michiel van Mussher, 1698

A count dare not say no to the tsar’s best friend. Menshikov left with Martha. He was younger, jollier, and enjoyed luxury and comfort. No doubt his house was better appointed, and his bed was softer than that of the field marshal. So lively and clever was this young woman, that soon everyone began to wonder—who was in charge of Menshikov’s household, he or his new mistress?

When Tsar Peter stopped at Menshikov’s, he could not help but notice the affable Martha. Why doesn’t she bring a candle to his room? In the morning, Peter returned Martha to his friend and left her a ducat—a mere pittance! Once the tsar left, Martha and Menshikov could live happily ever after—like Cinderella and her Prince. Couldn’t they? Not at all. Our Russian Cinderella had just started on her path to happiness. Peter soon returned and left again—this time with Martha.

Shmarinov. Peter Meets Martha. Illustration to Peter I by A. Tolstoy

There was no honeymooning for the couple. Peter left his beloved to be supervised at first by a relative, and then by his sister, Natalia, and went off to war. It was Natalia who taught Peter’s new mistress Russian as well as palace etiquette. Martha converted to Russian Orthodoxy and was christened Catherine.

Even to a military man as indifferent to comforts as Peter, leading troops and wielding swords became tiresome. “Hasten and come here! Catherine, my dear, come immediately!” He wrote her.

Day or night, in any weather, on horrible roads and rickety bridges, on horseback or by carriage, often pregnant, Catherine rushed to be with him. She warmed herself by campfires, washed from a bucket, and slept on a camp bed. To imagine that her endless pregnancies would be an excuse for not being by Peter’s side? Never! He needed her. And so did his entourage who relied on her to deal with his violent rages.

Whether at a military camp or at the palace, Catherine was the only person who was not afraid to approach Peter during his terrifying fits of rage. Witnesses remembered that he was soothed merely by the sound of her voice. With his head on her lap, he would instantly fall asleep as she sat for hours, with a smile on her face, and combed her fingers through his hair. He always awoke refreshed and in a good mood. (M. Shankov. Peter I Resting.)

Peter wanted to marry Catherine in 1710 but had to postpone the nuptials because of war with the Turks. He had her accompany him and instructed everyone to regard Catherine as his lawfully wedded wife and the future Russian Tsarina.

Peter’s Pruth River Campaign (aka Russo-Ottoman War of 1710-1711) turned outto be a disaster. His 38-thousand army fought against 190 thousand enemy troops. His Council of Generals decided to negotiate a ceasefire with the Ottoman Grand Vizier. How to convey this message to the belligerent and unpredictable Tsar? They agreed on Catherine since she was the only person allowed to enter his tent. (P. Stroli. Catherine Tries to Convince Peter to Sign a Peace Treaty with the Turkish Vizier. Circa 1800-1802)

Legend has it that Catherine offered the Grand Vizier her jewelry to grant the Russian Tsar and his troops a retreat. It is unclear if there had been a bribe, but the retreat was granted.

In 1712, once the unsuccessful campaign was over, Peter and Catherine married.

The Wedding Dinner of Peter I (figure 1) and Catherine I (figure 2) by Zubov

Ten years later, Peter remembered Catherine’s support and military contributions during those “disastrous times” when he crowned her Empress of Russia in May 1724.

Peter ordered a crown—the first one in the Russian Empire—for Catherine’s Coronation.

Peter and Catherine had at least 8 children, all born out of wedlock. Only two daughters, Anna (L) and Elizabeth (R), lived to adulthood.

Shortly after Catherine’s Coronation, Peter learned that she had been unfaithful to him. The offender, William Mons, was immediately arrested, accused of briberies and promptly beheaded.

Peter’s tragic discovery was wrapped in double irony. First, William Mons was the young brother of Anna Mons, Peter’s lover while he was still married to his first wife, Evdokia. Second, Anna was also unfaithful to Peter. (D. Shmarinov. The Ball at the Monses. Peter I and Anna Mons. Illustration to Peter I by A. Tolstoy.)

Peter (16) and Yevdokia (20) had an arranged marriage in 1689. Peter quickly lost interest in his wife and started an affair with Anna Mons. Despite Yevdokia’s protests, in 1698 he sent her to a monastery. Peter might have married Anna, had he not discovered that she was having an affair. (L) A drawing from a book of poetry presented to Peter as a wedding gift. (R)

Who knows what Catherine’s fate might have been had Peter not fallen ill and died several months later, in February 1725? He had unilaterally decreed that he would name his successor. His last words were “Leave everything to…”

Whom did he have in mind?

Many among the old nobility were in favor of Peter’s grandson, Peter Alexeyevich (Peter II.) But the Guards who adored Peter the Great burst into the Senate Assembly and proclaimed “Revered Mother” Catherine the new Empress. Russian Cinderella’s journey was now complete.

She ruled for only two years until her death in 1727. Except for several years, women would continue to occupy the Russian throne until the end of the century.