Royal and Divine

The Life of Matilda Kshesinska, Prima Ballerina and Mistress of the Tsar

PROLOGUE

Matilda Kshesinska was about to show her students the small school theatre when a loud voice made her stop.

“They are here!” somebody cried. The sound reverberated through the deserted classrooms of the Imperial Theatrical School. The voice sounded familiar. Hadn’t she heard it sixty years ago, in 1890? At the age of seventeen, she had danced here before Emperor Alexander III and his family at her graduation performance.

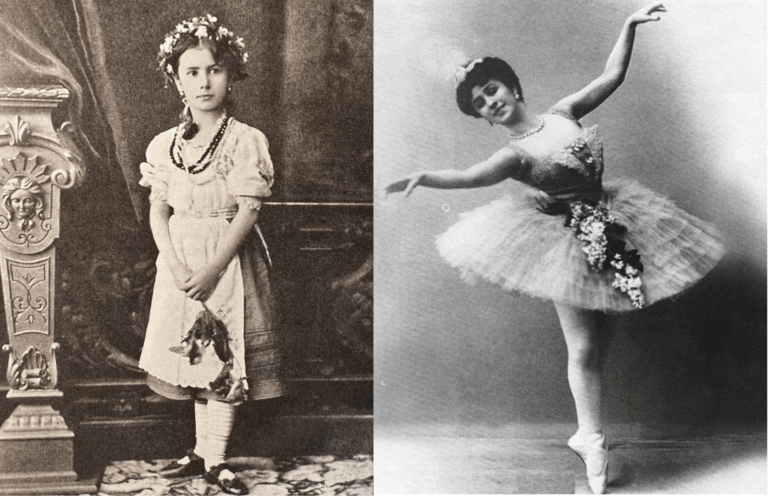

Matilda Kshesinska was 8 years old when she began her studies at the Ballet Department of the Imperial Theatrical School in St. Petersburg. She would become the only Russian prima ballerina assoluta to dance on the imperial stage.

“They are here!” another voice rang above their heads.

Matilda wanted to see who had said it, but her eyes refused to focus.

“Who is here?” she finally managed to ask.

“The royal family,” came the quick reply.

“Impossible,” Matilda said.

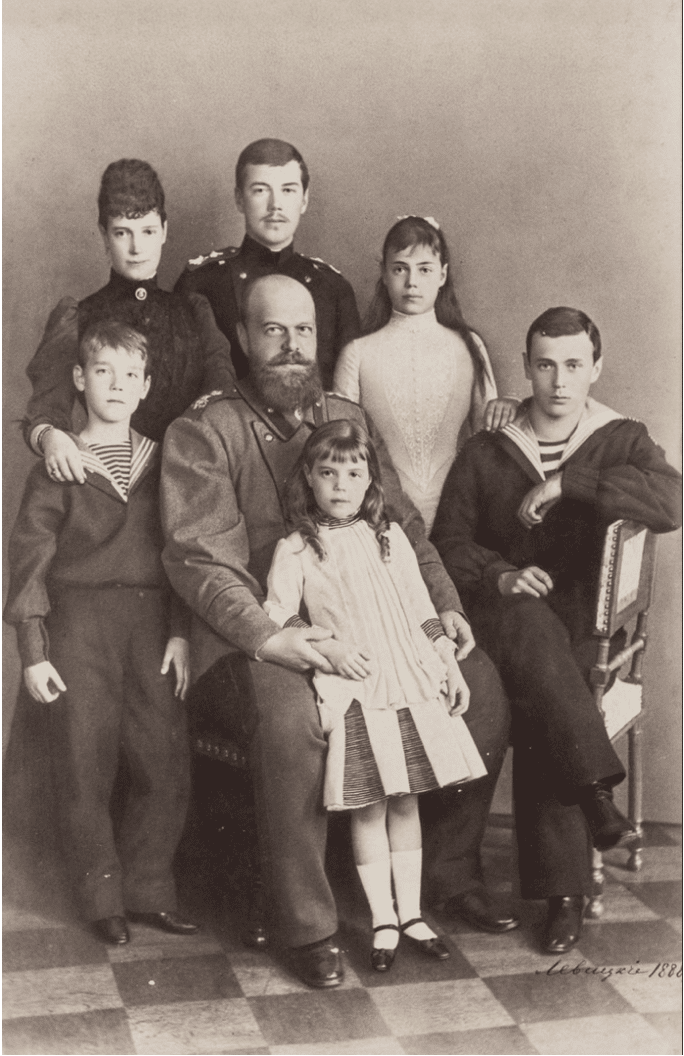

Emperor Alexander III and his family liked to attend graduation performances at the Imperial Theatrical School. (Future Tsar Nicholas II is in the back row.)

Before Kshesinska knew it, the crowd had swept her down the marble stairs, into the foyer. An a cappella choir started her favorite hymn:

Christ has risen from the dead,

Trampling down death by death.

Had the emperor already arrived at the front door? Most people trembled at the sight of his colossal, bear-like figure, but not Matilda. She adored him. When I see him, I will kneel and kiss his hands! she thought. Tears blurred her vision, but she kept on moving down with the stream of people and never even bothered to glance down at the steps. Matilda knew them by heart, knew every single imperfection in them from the time she was an eight-year-old student here at the School. She reached the foyer and stopped. The front doors stood ajar. Outside, a storm raged; the wind roared; torrential rain poured down.

“They cannot enter,” somebody cried.

“Of course, they cannot enter. They are all dead,” she said and woke up.

Matilda Kshesinska in exile

Seventy-seven-year-old Matilda Kshesinska had just regained consciousness after surgery to fix her broken leg. She was at the American Hospital in Paris. The year was 1950. Matilda had outlived them all, the emperors and the empire. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution had executed her loved ones, swallowed her fortunes, seized her home and destroyed her country. They existed now only in her memory.

Once the fog of anesthesia dissipated, Matilda asked the nurse for a pen and paper. Pain clawed its way up and down her leg, but what ballerina did not have pain as her constant companion? Matilda ignored it. She felt as if some force were guiding her to put down what she remembered, to resurrect the vanished era and the dead. If only she still had the letters from the crown prince! Without them, would the readers believe how much in love she and Nicholas were? The loss of that priceless correspondence was overwhelming, but Kshesinska would not let it stand in the way of her story. She had never let anything, or anyone stand in her way. Matilda propped herself up in the hospital bed and began to write.

PART 1

Chapter 1

FAMILY LEGEND

Most writers begin their memoirs by recalling a factual, life-changing event and then use it as the cornerstone of their story. Matilda Kshesinska started hers with a legend: a narrative in which truth and fiction are so intertwined, you could not separate one from the other.

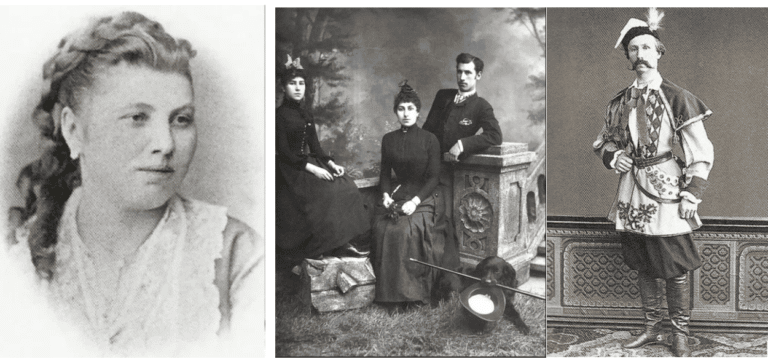

Matilda came from a theatrical dynasty. Her mother, Julia (L)and her father, Felix (R) were ballet dancers. All three of their children followed in their footsteps. (Center, L to R: Matilda, Julia, Joseph)

The legend started in Poland, sometime in the eighteenth century, one hundred and fifty years before Matilda’s birth when a twelve-year old boy, Voichek Krasinski, lost both his parents. The little orphan, who would one day become Matilda’s great-grandfather, inherited his father’s title, Count Krasinski, and the family estate. One would think that the youngster would live with his uncle, but, according to the story, he was left in the care of his French tutor, a kind and caring man, who over time became his good friend.

We shall never know why the legend did not preserve the tutor’s name. Wasn’t he the story’s true hero? When the tutor learned that Voichek’s jealous uncle decided to kill the young count and usurp his title and fortune, he quickly gathered some papers and clothes, grabbed the child and left the estate. The tutor brought Voichek to his family home in Neuilly, France and gave the child a new last name: Krzesiński. Why Krzesiński? Maybe it was his mother’s maiden name. Maybe it sounded like the boy’s real name, without revealing it. That way the vengeful uncle could not trace their escape and Voichek would remain safe. Maybe, when he grew up, he would go back to Poland and claim what was rightfully his. Would the old tutor live to see that glorious day?

Painting by Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski. For illustration purposes.

He did not. Years went by and Voichek married a pretty Polish émigrée named Anna. After the birth of their son, Yan, the family decided to return to their homeland. Certainly, the uncle was dead by now and they could seek restitution. Voichek gathered the few papers his tutor had brought with them and the Krzesińskis embarked on their journey. Upon their arrival in Poland, Voichek learned that the villainous uncle had declared him dead and had become the new Count Krasinski, owner of great riches and a beautiful estate.

Voichek’s dream of reversing his fortunes did not come true. Maybe it was because there had never been any estate or title to begin with. Or maybe it was because during the fifty years of his absence, multiple wars had redefined or obliterated property rights. Fires and other calamities had destroyed most church records. The papers that the French tutor had saved were insufficient to reclaim what once had belonged to Voichek. Why did he decide not to return to France? The legend is mute on this question. All we know is that Voichek and his family settled in Poland.

Voichek’s son Yan—Matilda’s future grandfather—grew up to become the first tenor of the Warsaw opera and a violin virtuoso. Some even said that he performed in concerts with Niccolò Paganini. The public loved him, and the Polish king called him “my nightingale.” When Yan grew older, he gave up opera and became a successful dramatic and comedic actor. He died at the age of one hundred and six from carbon monoxide poisoning and was survived by his three children, Stanislaw, Matilda and Felix, who would become Matilda’s father.

Why did Felix, when he moved to St. Peterburg, change his factitious name Krzesiński to Kshesinski, and not his real noble name, Krasinski? And why did he, the youngest of the siblings, inherit Yan’s chest with the papers that proved the family’s aristocratic past? Yan had instructed him to safeguard the chest “because it would open new ways.” Why then did Felix give it to a relative for safekeeping? Matilda’s legend does not answer any of these questions. All we know is that the chest was lost, and no one ever saw it again. What little proof there had been of the Krasinkis’-Krzesińskis’-Kshesinskis’ aristocratic past vanished forever.

As Felix’s three children—Julia, Joseph, and little Matilda, known as Malya in the family—grew up, the older siblings realized that their father’s captivating story was nothing but a fairy tale. But Malya always believed it to be true. The chest with the precious papers might have been lost, but Felix still had a small memento that proved their family’s aristocratic roots—a ring with a black raven from the Krasinskis’ coat of arms. Malya felt the blue blood of Count and Countess Krasinski flowing through her veins. She saw a sparkling crown resting smartly on her head. As a child, she could not have known that such rings were common in Poland. As an adult, she would choose not to mention that fact in her Recollections. Why spoil the magic? Kshesinska was determined to restore the Krasinkis’ noble title and riches. Malya did not yet know how to do had no doubt she would find a way.

Various versions of the so called Ślepowron coat of arms had been used by many Polish-Lithuanian noble families.

Chapter 2

THE MAZURKA

From early childhood, Malya knew that everybody called her father “the King of Mazurka.” No one could perform or teach this fashionable dance better than Felix Kshesinski.

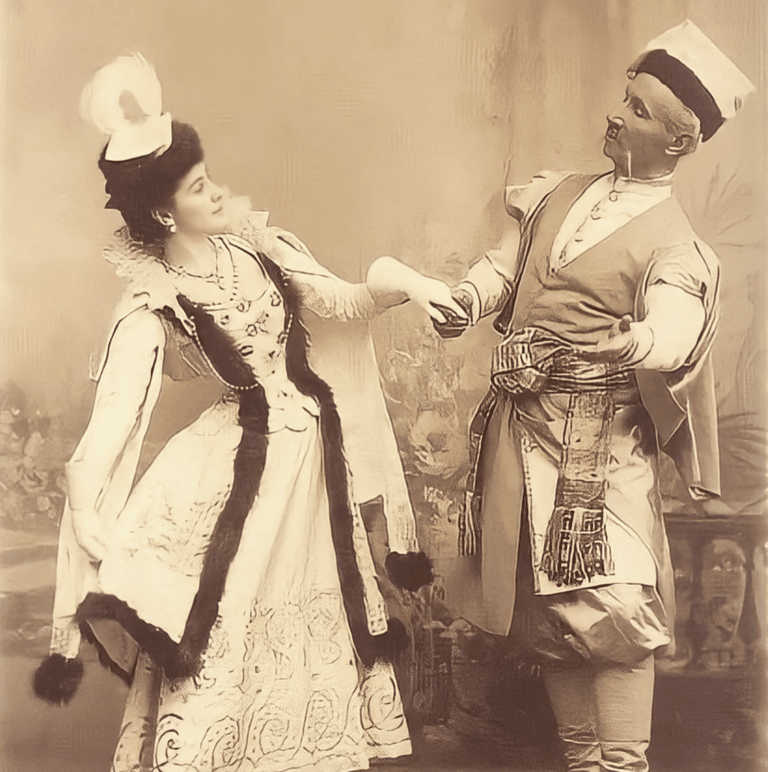

Felix Kshesinski taught the mazurka to members of the royal court and aristocracy. Theatrical audiences loved to see Felix and Matilda perform the dance together.

On stage, Felix’s character dances were just as expressive as his mazurka. In the Little Humpbacked Horse his evil Khan drew more applause than the heroes. Felix decided that this popular ballet would be perfect for three-year-old Malya.

Having seated her in an armchair in the actors’ box he asked, “Are you comfortable?”

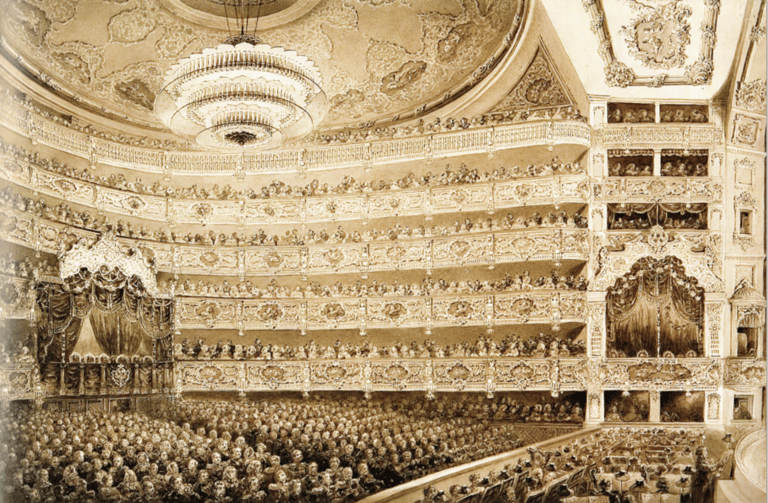

“Yes, Papa,” Malya said. Her dark eyes took in the grandeur of the St. Petersburg Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre. The enormous crystal chandelier—it was bigger than the sun!—shone high above and made the auditorium gleam as if it were made of pure gold. And the box was right on the stage! She would be able see everything!

The St. Petersburg Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny (Russian: Stone) Theatre was the principal venue for the Imperial Russian Opera and the Imperial Ballet. In 1886, the theatre was declared unsafe. It was torn down to make way for the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Felix asked some older girls, students from the Theatrical school, to keep an eye on his daughter. It was Malya’s first visit to the theatre. He did not want her to become frightened or feel lonesome.

“Watch for me on stage,” Felix said and gave Malya a kiss on the forehead. “I’ll fetch you after the performance.” She nodded but her attention was already elsewhere. Theatergoers were starting to enter, many of them with children, and Malya slid out of her chair and leaned over the side of the box. Now, everyone would notice the lovely ribbon in her hair and her pretty dress. She barely had time to return to her seat before the lights dimmed and the orchestra began to play the overture.

When the show concluded, everyone rose and applauded as the dancers took their bows. “Bravo! Bravo!” people cried. Malya clapped her hands until they began to hurt.

The older girls reminded Matilda to wait for her father and left. The theatre slowly emptied. Workers extinguished most of the kerosene lamps and began to clear the stage and prepare for the evening performance. From her seat Malya watched as they moved and tested the props. Right before her eyes, sunny days turned into moonlit nights, gusts of wind shook the walls and sinister storms rolled in with heart-stopping lightning and thunder. It was pure magic. She did not want it to end.

END OF EXCERPT