Everyone called her Rose. What a pedestrian name for such a majestic, elegant woman! Forever a romantic, 26-year-old General Napoleon Bonaparte chose to call the widowed Vicomtesse de Beauharnais Josephine. The name sounded more poetic to his Corsican ear.

Born in Corsica and educated in Paris from the age of nine, Napoleone Buonaparte was a graduate of the prestigious École Militaire where he studied to be an artillery officer. For his name to sound more French, he changed it to Napoleon Bonaparte when he was 27.

Marie-Josèphe-Rose Tascher de la Pagerie (aka Josephine) married nineteen-year-old Viscount Alexandre de Beauharnais when she was sixteen. The groom was eager to receive 40,000 livres to be paid annually upon his marriage. The bride could not wait to leave her parents’ failing plantation in Martinique and move to Paris. The couple had a son, Eugène, and a daughter, Hortense, but their marriage proved to be a disaster. They officially separated and fought endlessly over their children.

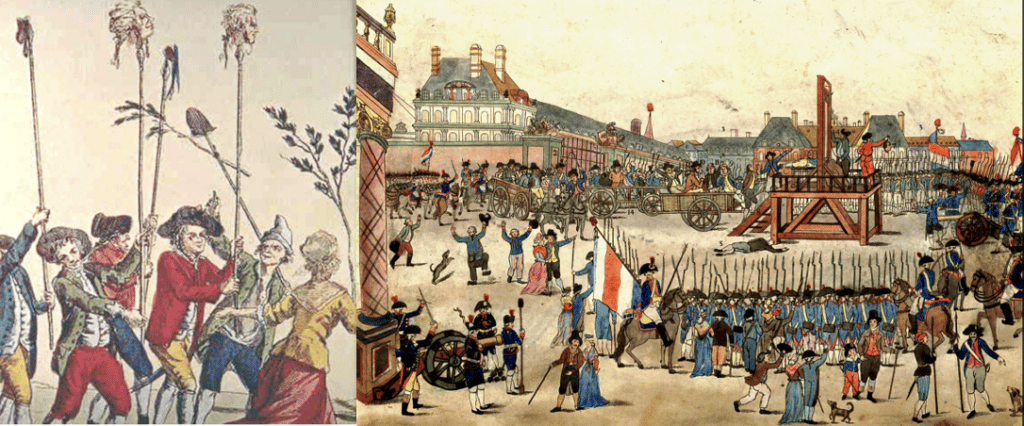

As members of aristocracy, Alexandre and Josephine were jailed during the rule of Robespierre. Alexandre was guillotined. Luckily, Josephine was not executed. The Reign of Terror came to an abrupt end and she was released. (Left: Aristocratic heads on Pikes. Right: The Execution of Maximilien Robespierre, which marked the end of the Reign of Terror.)

How did Napoleon and Josephine meet? Family lore offers a maudlin story about an encounter between Eugene, Josephine’s fourteen-year-old son, and General Bonaparte.

Having defeated a monarchist uprising in Paris, Napoleon was promoted to Commander of the Army of the Interior and oversaw the confiscation of civilian weaponry. Eugène came to the General’s headquarters to ask if he might keep his late father’s sword. Moved by the boy’s plea, Napoleon granted his request. Josephine, Eugène’s grateful mother, came to thank the General for his kindness. The rest was history.

The reality was much more prosaic. Saved by Napoleon from being deposed—and decapitated—by royalist insurgents, Paul Barras, the head of the new French Government, took Bonaparte under his wing. He introduced his brave but untutored protégé to the highest circles of Parisian society. It was there that Napoleon first saw Josephine—one of the salons’ reigning queens—and one of Barras’ lovers. Despite the competing stories of how they met, the happy ending was the same.

While Josephine had no compunction about sharing her bed with Napoleon, she did not share his passion. Awkward, with a sallow complexion, long, unkempt hair and scabies, Bonaparte did not impress the aristocratic, socially adroit Josephine. He, on the other hand, was overwhelmed by her charm and sexual prowess.

Napoleon to Josephine:

February 23, 1796

My waking thoughts are all of thee. Your portrait and the remembrance of last night’s delirium have robbed my senses of repose. Sweet and incomparable Josephine, what an extraordinary influence you have over my heart.… I shall see you in three hours. Meanwhile, my Dolce Amore, accept 1000 kisses, but give me none for they fire my blood. N. B.

Femme fatale, Josephine could still charm any man, but her years of youth were over. She was thirty-two, a widow with two children and very expensive tastes. It was time to think of stability.

An astute politician, Barras convinced the two lovers that marriage would benefit them both. Faced with perpetually growing debts—Josephine would end up spending more on clothes than Marie Antoinette—she accepted Napoleon’s proposal of marriage. The bride wisely kept her financial woes to herself and even implied she would be receiving a fortune from the Martinique estate. Yet Napoleon—the general was no fool—had uncovered her devious ploy. A heated argument ended with her tears and his forgiveness.

Since the French Revolution abolished church weddings, Napoleon and Josephine married in a civil ceremony. The bride wore a republican tricolor sash over her white muslin wedding dress. The groom, two hours late, arrived with a gift: a medallion engraved with the words “To Destiny.”

Six years her junior, Napoleon added a year and Josephine shed four, which made them both twenty-eight. Napoleon later joked that “According to her calculations, Eugène must have been born at the age of twelve!”

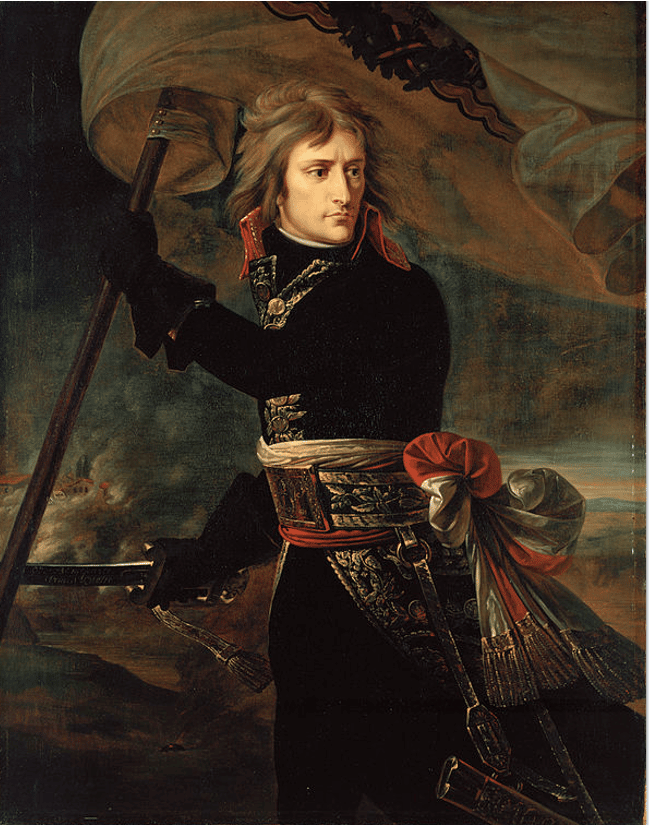

Napoleon’s late arrival for his nuptials was not caused by cold feet but rather by a matter of state importance. Barras had appointed General Bonaparte to lead the Army of Italy—Napoleon’s own army—against Austrian troops. After a forty-eight-hour honeymoon, Napoleon left for army headquarters in Nice. He was horrified to discover that the soldiers, starving, shoeless, in makeshift uniforms, were in no condition to fight.

With Bonaparte always at the head of his troops, one victory followed another. Daily, sometimes right after exhausting battles, the general sat down to write voluminous, passionate letters to his beloved Josephine.

I have not spent a day without loving you; I have not spent a night without clasping you in my arms; I have not drunk a cup of tea without cursing the glory and ambition which keep me from the heart of my very being. In the midst of my activities, whether at the head of my troops or inspecting the camps, my adorable Josephine stands alone in my heart, she occupies my mind and fills my thoughts…

Josephine hardly cared enough to write back. Napoleon was frantic with worry. Had she fallen out of love with him? Was she ill? A mere ten pages from her would console his tormented heart. Would she write to him immediately? Would she come to see him? What was she doing in Paris that kept her so far away from him?

The answer was simple. Josephine had begun an affair with Hippolyte Charles, a witty, fun-loving hussar, nine years her junior. Unfortunately, the transgression did not stop there. The couple had invested in a company of war-profiteering army contractors, who were glad to have General Bonaparte’s wife among their ranks. When Josephine finally traveled to see Napoleon, she did not think twice about bringing Hippolyte with her…

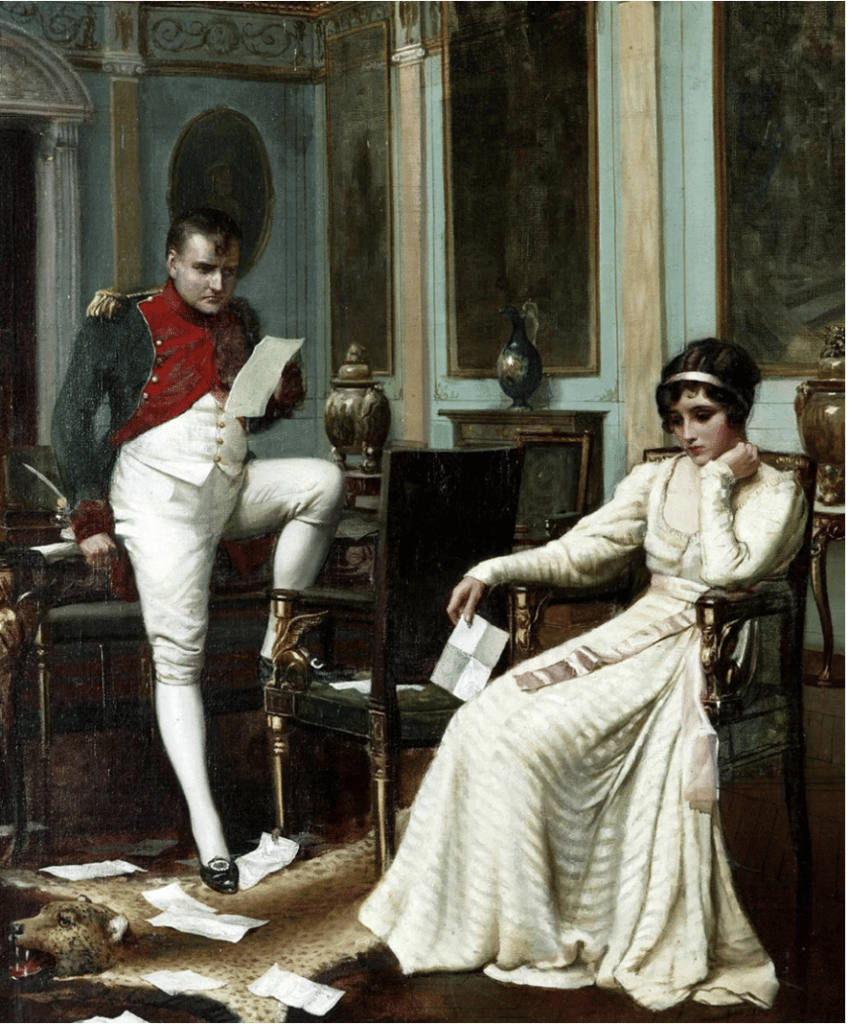

With his wife’s flamboyant past and present rumors of her conduct, Napoleon ordered Josephine’s mail delivered to him—what a humiliation for her!

Napoleon’s family found Josephine too old, flashy and glib and never accepted her. Therefore, it is hard to imagine that Joseph, Bonaparte’s older brother, who traveled with Josephine and Hippolyte and witnessed their relationship, did not share his observations with Napoleon. Perhaps the victorious general was not ready to face the truth and be defeated by his own spouse.

Josephine denied any wrongdoings and Napoleon chose to believe her. He returned to Paris a hero who had conquered all Northern Italy and unequivocally defeated the larger and stronger Austrian army. His trophies were not limited to lands, prisoners and cannons. Among them were unique works of art, fine clothes and jewelry—the best of which he bestowed upon his wife.

Napoleon’s victories and spreading fame threatened Barras’ rule. The Directory decided to send Bonaparte to seize Egypt from the Sultan of Constantinople. A defeat would tarnish the general’s stellar reputation. A victory would disrupt the trading routes of enemy Britain. The statesmen concluded they could not go wrong. If only they knew what awaited them!

Though Napoleon’s first battle in Egypt was an astounding victory, he eventually lost the war there. Leaving his army behind, he returned to France in October 1799. (Antoine-Jean Gros, battle of the Pyramids, 1810.)

Paris welcomed Bonaparte as the long-awaited hero. A few defeats in faraway Egypt were nothing compared to his past victories in Europe. He returned to witness a bickering, corrupt Directory, looting street gangs, political unrest, territories he had won seized by enemy armies, and the country on the brink of war with a new coalition led by Britain, Russia and Austria.

The drastic conditions in Paris were not Napoleon’s only worry. While in Egypt, he learned of Josephine’s unsavory dealings with army profiteers. He also knew with certainty that she was unfaithful to him. It was the end of their marriage.

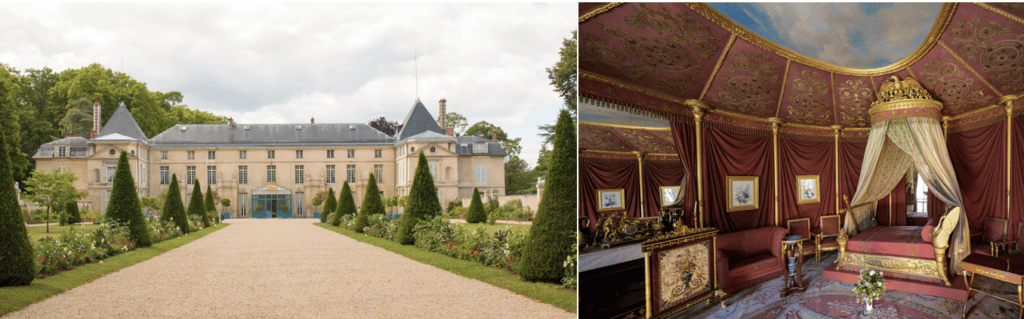

While Napoleon was in Egypt, without asking his permission, Josephine borrowed 300,000 francs and purchased Château de Malmaison. This was a rundown 150-acre estate seven miles west of Paris. Grudgingly, Bonaparte paid for the estate. The restoration cost him another fortune. (Right photo, Josephine’s bedroom. By permission from https://commons.wikimedia.org)

While the French celebrated Napoleon’s return with parades and cheering processions, Josephine finally realized that her husband was a hero and that he was going to divorce her.

Caught unawares by Napoleon’s swift return, Josephine hurried from Malmaison to their home in Paris. Pushing servants aside, she ran upstairs to her husband’s room. It was locked. For hours, she knocked and pleaded. Then she sat by the door and wailed. At nightfall, she fetched her children. Together, the trio raised this operatic performance several notches until—oh glorious moment!—he opened the door…

Historians differ as to why Bonaparte forgave Josephine. Was his love for her still strong? Did he decide to stay married for political reasons? Was it a combination of both? In any event, the couple reconciled, but the dynamics of the marriage underwent a drastic reversal.

From that day forward, Josephine would be forever faithful to her illustrious and powerful husband. Napoleon, on the other hand, would take endless lovers while he demanded his wife’s docile compliance. Rejected by Hippolyte, the merry hussar, Josephine accepted the arrangement.

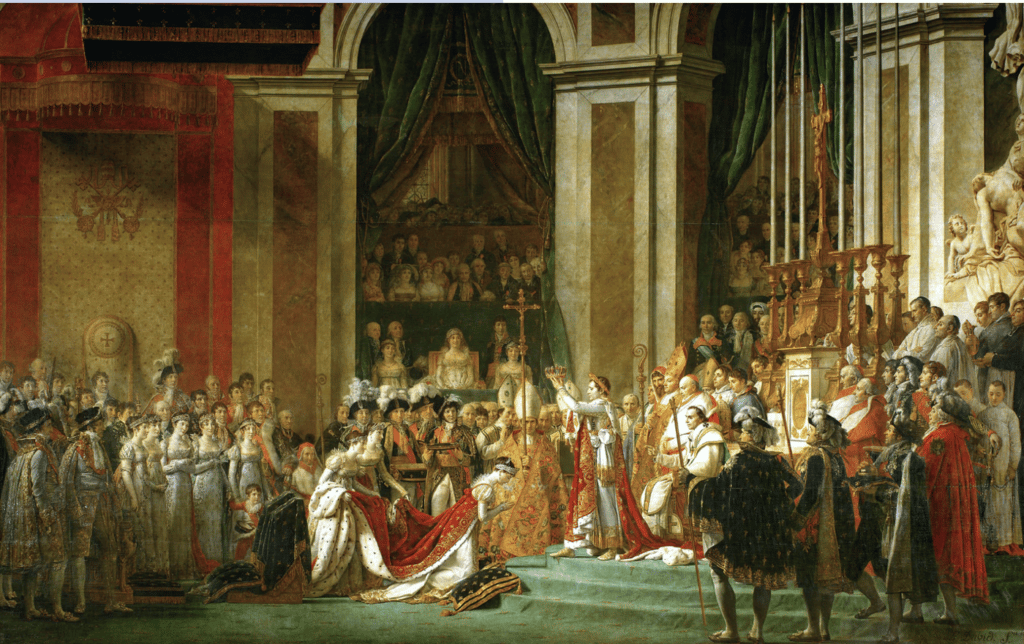

Only a month after his return from Egypt, in November 1799, Napoleon and his allies staged a coup-d’état, overturned the Directory and formed a new regime—the Consulate. Eventually, Napoleon was elected to the position of First Consul and bestowed himself with dictator-like powers. Five years later, he declared himself Emperor Napoleon I of France.

Napoleon personally crowned Josephine as Empress of France.

In charge of the country, Napoleon set out to reconquer France’s lost territories. Devastated by her husband’s continuous affairs, in a reversal of fortune, Josephine now begged to accompany him. Bonaparte demurred. He did not want her by his side.

The famous painting by Jacques-Louis David depicts Napoleon crossing the Alps. This unexpected maneuver surprised Austrian troops. Once again, Bonaparte forced Austria to surrender.

As a result of his spectacular victories, Bonaparte returned to France a living legend. Josephine worried: with Europe at his feet, Emperor Napoleon I needed an heir. Who was to blame for their not having children?

In 1810, Bonaparte’s lover, the beautiful Marie Walewska (L), gave birth to their son, Alexandre (Center.) There was no doubt: Josephine could no longer bear children.

In 1810, citing state interests, the couple divorced. Josephine maintained her title as empress with all its privileges. Besides agreeing to pay her debt of 2 million francs, Napoleon granted her an income for life of 3 million francs. In addition to Malmaison, he gave Josephine the Élysée Palace and the 14th-century Chateau Navarre in Normandy.

On her return to Malmaison, she succumbed to melancholy and tears. When Napoleon visited, as he had promised, she clung to him like an abandoned child. In his letters, he urged her to find courage and seek happiness. Though Josephine knew that he was to wed again, she was crushed upon hearing the news of Bonaparte’s betrothal to Marie Louise, the 18-year-old Archduchess of Austria.

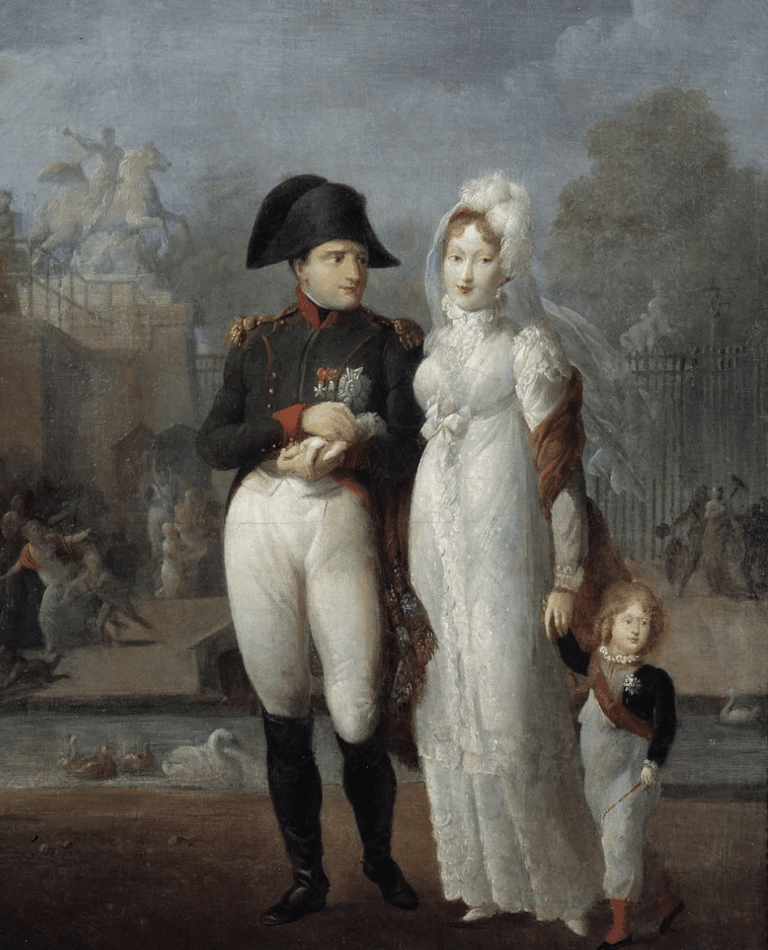

A year later, Marie gave birth to a baby boy, Napoleon II. The child received the title of King of Rome.

Though Napoleon was happy with Marie Louise, Josephine remained the love of his life. He had always regarded her as his lucky charm both in war and peace. With her out of the picture, Bonaparte began to lose military battles. In 1812 his army suffered a disastrous defeat in Russia. Other losses followed. In 1814, Napoleon was forced to abdicate and was exiled to Elba, an isle off the coast of Italy. Marie Louise had no intention of visiting him there. And Josephine? Bonaparte believed she would have joined him in his exile. Was it wishful thinking? Josephine died only weeks after he disembarked in Elba. She would never learn of her ex-husband’s daring escape and his repossession of the French throne. Napoleon managed to raise a new army, which was crushed at the Battle of Waterloo. Once again, he was forced to abdicate and was exiled to the remote island of St. Helena. Bonaparte died there six years later, at the age of 51. Legend has it that his last word was Josephine.

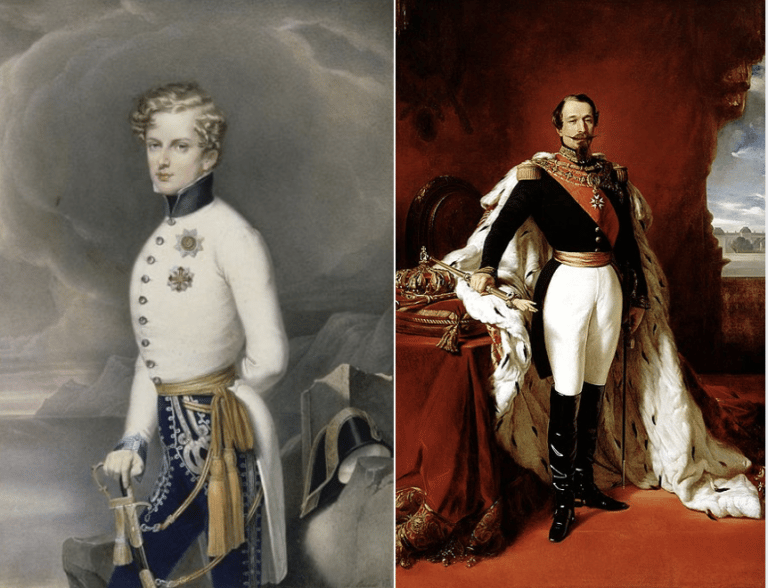

Bonaparte’s only legitimate son, Napoleon II (L) , died of tuberculosis at the age of 21. It was Josephine’s grandson, Napoleon III (R), who became Emperor of the French.

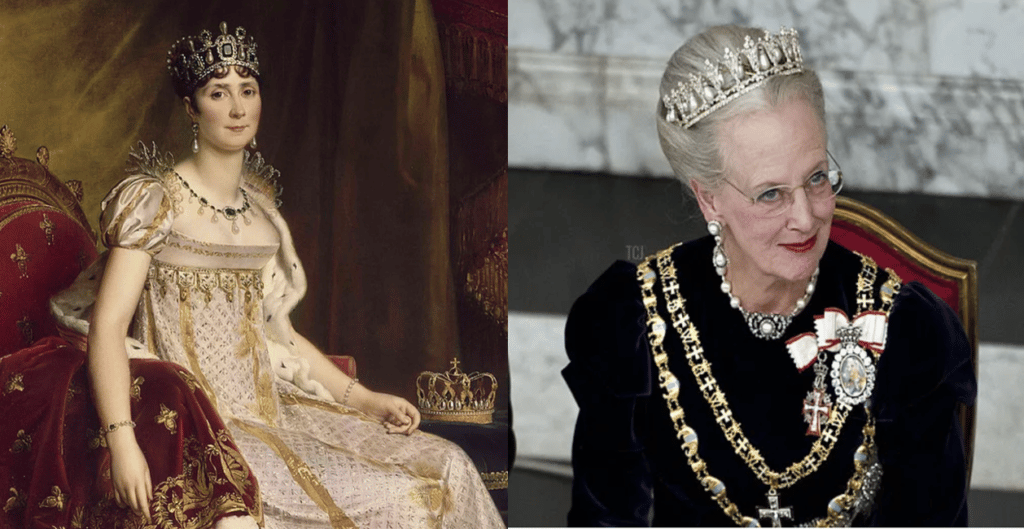

Today, Josephine’s direct descendants sit on the thrones of Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Luxembourg. (8 generations separate Josephine and Queen Margarethe II of Denmark.) Getty images.

2 thoughts on “Napoleon and Josephine: Madly in Love Forever”

Very well done and most enjoyable!

Extremely well researched! Read and get the true story.